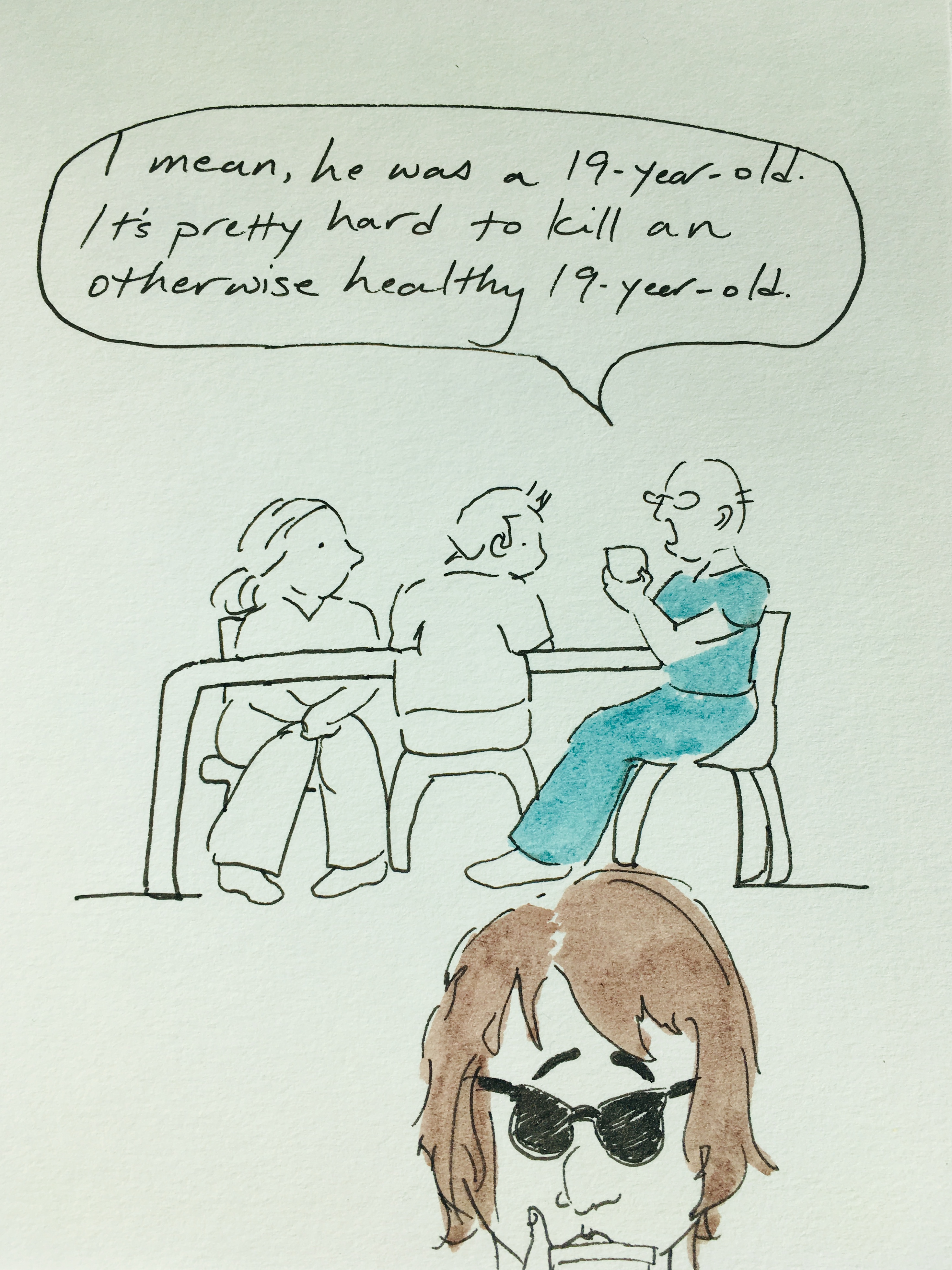

For a time now, I’ve been able to put cancer behind me. I’m doing–and thinking about–other things. But this Friday, I have my first post-treatment CT scan, and it’s looming large on the horizon. I keep rehearsing the afternoon’s appointment in my head by recalling how things went down the first time. Drinking that awful barium sulfate solution, alone, in a freezing cold room; the brisk manner of nurses and lab techs; lying on yet another narrow table; feeling the contrast dye saturate my veins; repeating the mantra I said to myself, before, as the machine pivoted around me: My body is a dark city, my body is a dark city. Like London during the blackouts of WWII, I don’t want it to light up. (Obviously, my understanding of how these things work is vague, but I believe the radiologists are looking for some kind of “activity”–for cancer cells to react to the chemicals coursing through my body by luminescing.)

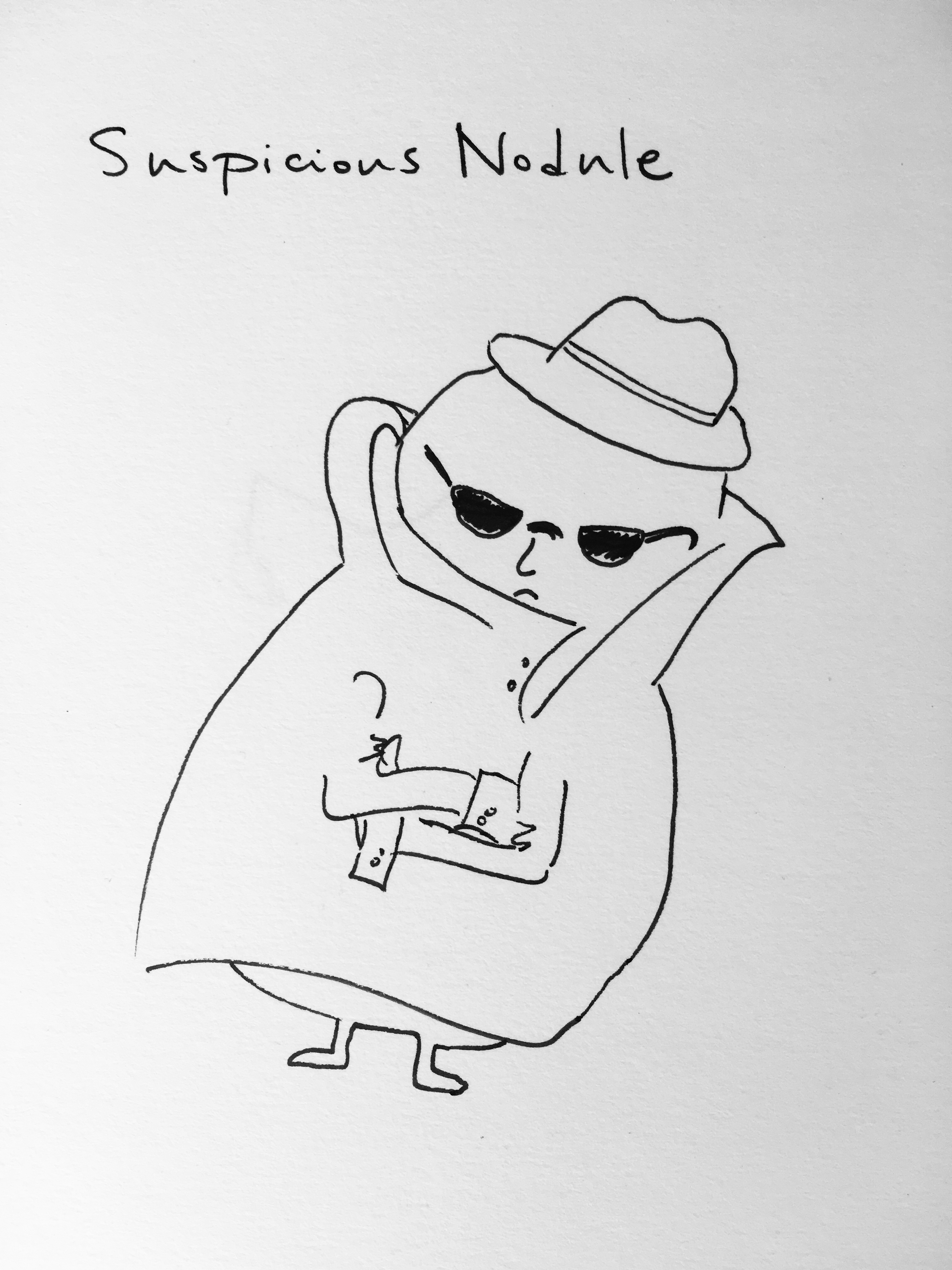

For some reason, my mind also keeps going back to my initial pathology report. I don’t know why doctors give these to patients; mine consisted of a dense paragraph of medical jargon followed by this stand-alone sentence, in all caps:

THE LESION IS MALIGNANT.

Reading it felt like the closest I might ever come to visiting an oracle. But what seemed, at the time, like a fixed decree–an intractable fate–has since revealed itself to be a bit more pliant. Much can still be done in the wake of such things; choices can still be made. Which may be why I’ve been questioning some of my own lately. Small ones, like becoming irritated in traffic, or with the endless stream of students filing into my classroom to borrow my stapler this morning. Do I, alone, have the earth’s last functioning stapler, I wondered. And then I took a deep breath, a proverbial step back. I do a lot of that now. Trying to notice how I’m responding to certain things and why. Trying to hold onto the perspective that the past nine months has brought, though it was dearly purchased (does perspective ever come cheaply?). Is this worth the worry or frustration it’s causing me? Can I let it go? We all have so many heavy things to carry. Friday’s appointment is one of mine.