My daughter started kindergarten at her local public school this week. To pick her up in the afternoon, I have to buzz the office so that they can unlock the front doors and let me in the building. Once I’m inside, I cannot walk to the gym or playground or art room to fetch my daughter from after-care. A staff member has to escort her to the front office, where I wait, peeking through the window, like someone visiting a prison inmate. Yesterday afternoon, she was disappointed that I had come to pick her up so early; she wanted to go back out to the playground for just five or ten more minutes. “Pleeeeaaase!?” When I asked the receptionist at the front desk if I could accompany her back outside for a little while, I was told that I could not “because of the other kids out there.” I felt surprised, stung, even insulted, but acquiesced. As a teacher, myself, I understand that these are the more or less reasonable precautions our schools now take to protect children from the increasingly unreasonable world in which we all live.

Earlier the same day, in fact, I had completed a lengthy online training course ostensibly designed to help me respond to an active shooter situation, should one arise at my own school. It left me feeling afraid, numb, desperate, anxious and depressed. A second required active shooter training is scheduled for later this week. I dread it already. Front-loading our faculty in-service week with this kind of thing casts a pall over the year to come in a way I never experienced when I began my teaching career sixteen years ago. Already, I can anticipate a likely response: Things change; we must adapt. To which I reply, you’re right. Things do change. Why don’t we adapt our fucking gun laws?

Needless to say, I believe there are better ways to address this dire–and mounting–problem. The strategies implemented by our educational institutions seem to be, by and large, defensive ones. We’ve put up gates and locked them, we’ve installed cameras everywhere, easy entry to our buildings is barred, we’ve increased the number of armed security and police officers, we’re training our teachers and students to Alert! Lockdown! Inform! Retaliate! Evacuate! Subdue! Distract! Or any number of other acronym-ready imperatives. And these initiatives have not been without cost. Someone is–indeed, many are–profiting from them. We have clearly been sold on this as the solution, but I wonder if it might not, ultimately, compound the problem.

What kind of emotional and psychological climate are these quasi-militant protocols creating for the children and adults who spend the better part of their days in schools? What are they teaching us to believe and expect about the world, and about one another? Are they not normalizing the threat of violence? Worse yet, mightn’t they be fomenting it?

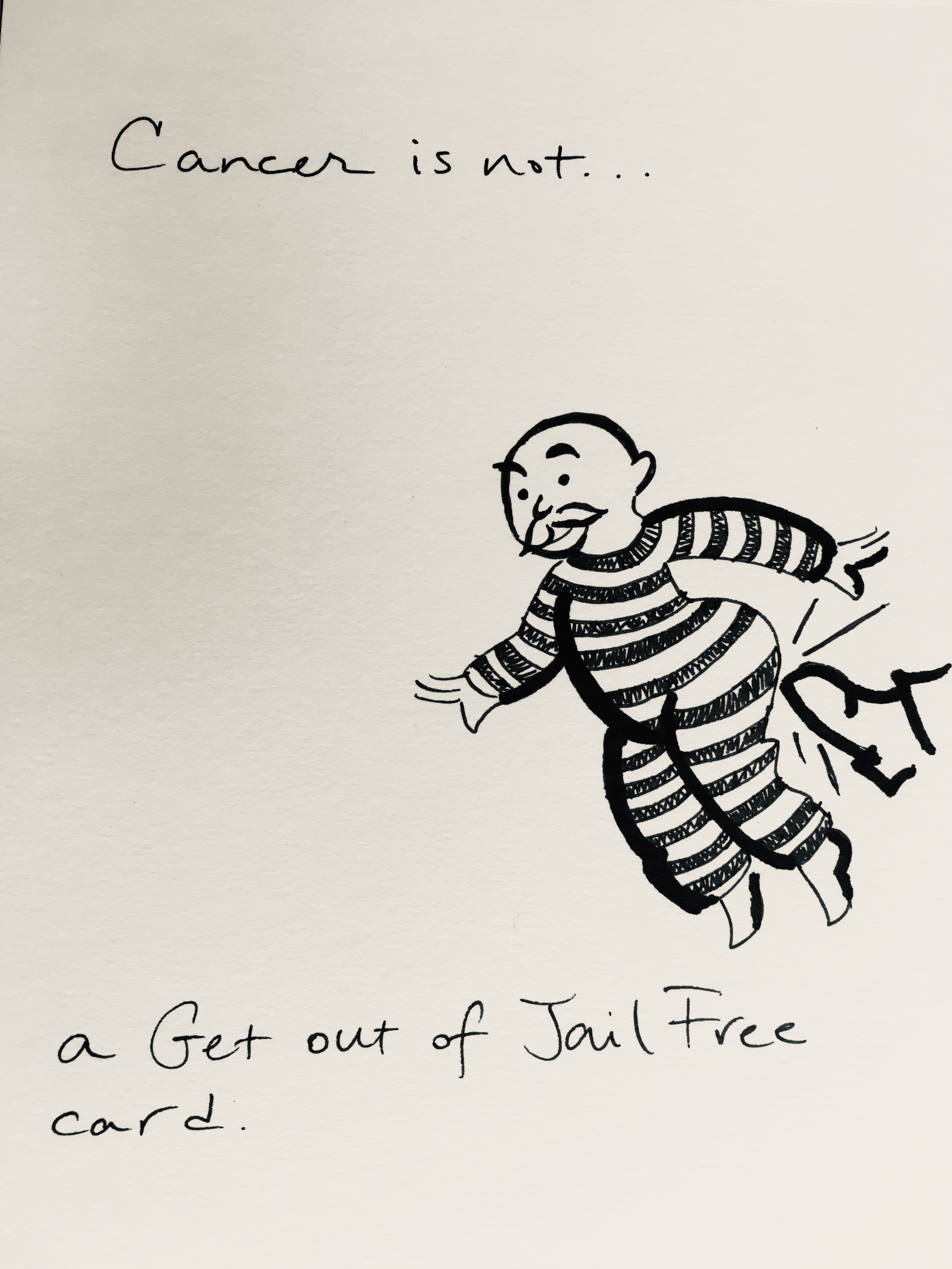

Not being able to enter my daughter’s elementary school; not being able to go see her, her peers, and her teachers as they participate in its daily life; not being able to get to know this new community to which I thought I belonged, is profoundly sad and strange. What do I feel when I buzz the ringer by the locked front doors of a public building, or wait in its office? Criminal, though I have done nothing. I feel alienated, suspect, and eager to leave. More importantly, as our children witness us go through these increasingly rote motions of caution and precaution, what do they feel? How do they internalize the glaring paradoxes of their environment? Why should they keep coming to a place that explicitly concedes, through all of these alarming new safety measures, that it isn’t, in fact, safe?