Today, I’m feeling better than I was. There’s a sense of accomplishment in getting over the hurdle that has been my first week of treatment. I know I still have a long way to go, but the past three months have already felt like a marathon of sorts. It’s helped tremendously to start seeing my therapist again. I first sought him out ten years ago, when I was deep in the trenches of graduate school. His office has changed location three times in the decade since then, and he’s helped me weather a number of storms over the years (postpartum depression and insomnia being a big one).

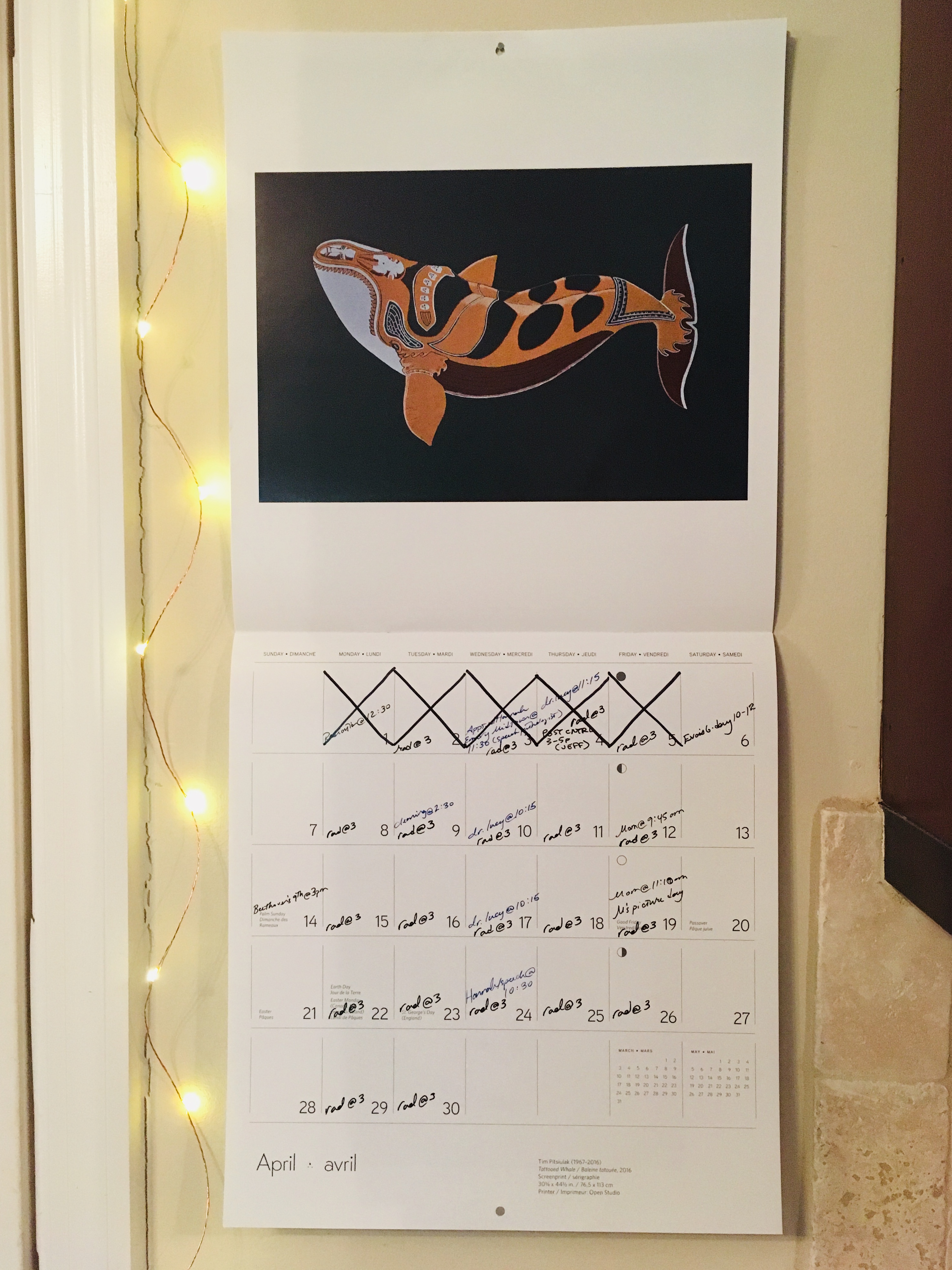

During our session yesterday, I was describing all of the strictures that have suddenly been placed on my life–the death mask, for one; the daily radiation appointment at 3pm; the host of other medical appointments that keep me bouncing from one doctor to another; the weird oral hygiene and physical therapy regimens; the temporary bans on alcohol and getting pregnant (ha! not something I necessarily want to do, but something I resent not having the choice to do), etc. But then, in the meandering course of our conversation, I realized all of the ways in which I’ve loosened up a bit, too. I’m reading four different books at once–something I never used to do. It always felt inefficient and oddly adulterous, like I was breaking a rule or something. I’m writing here in real time, when I formerly considered writing something that you labored over, privately, until you had the best possible rendition of what you wanted to say (and you had to know this, beforehand), sharing it only with a hypercritical cadre of editors and advisors. I’ve started drawing again for the first time in many years, I’ve had people over to our house even though it’s messy, and I’ve let go of certain vanities (speaking without a lisp and having a scarless neck, for example). Whatever. These things are a record of what I’ve been through–maybe even signs of an incipient transformation. It would be nice, I told my therapist yesterday (not to mention, ironic), if this experience was somehow freeing. If I could learn to sing in my chains like the sea.