Yesterday I received news that my annual CT scan was clear, and it settled in the strangest way. I felt relief, of course, but not the utter elation I’d expected. I say this because it wasn’t your typical scan; if clear, it would be likely be my last. And lo, it was! Yet I felt… so many different things. Which suggests that perhaps few emotions or experiences in life are unalloyed, though some have come close. Anticlimactic as the news was (sadly, medical test results aren’t sent with confetti effect), I still found myself wishing there was someone I could meet for a spontaneous drink to celebrate, but I didn’t know who that person would be at 2:45pm on a Monday. So, at a loss despite this seismic gain, I drove to pick up my daughter in the very same car in which I drove to pick her up after receiving my diagnosis five years ago with an uncannily similar sense of bewilderment. Wow, I thought to myself, I’m still here; I’m in remission; I’ve been cancer-free for 5 years. 5 years! It feels like a thousand lifetimes have transpired since my diagnosis in 2018–-so many awful and unexpected things have happened on both a global and personal scale that I’ve struggled to account for much of any of it. But I could no more account for the grace or good fortune that’s befallen me throughout my life, either. Account. That’s kind of funny. To whom? For whom? I suppose mostly for myself and maybe my daughter, in the event that she becomes curious about all of this when she’s older. I write these things down because then they live on the page, outside of me, and not solely inside, which can be overwhelming. And I share them here on the off chance that they might help someone else going through something similar, just as the few blogs I found my way to in the wake of my diagnosis helped me. To paraphrase James Baldwin, you feel alone in your suffering, and then you read. Or write. Or lean on others (those who helped me get here are countless and range from strangers to closest kin; I offer my gratitude to each and every one of them ❤️ ). Or walk the dog you once wondered if you’d live long enough to be able to have. Cheers to that.

Swim At Your Own Risk

How many times have I seen this sign and ignored it? Or worse, “No Swimming”? Maybe four or five; I remember them all. Lake Cochiti, a cement plant, Seville’s Guadalquivir River… They come to mind now because I spend a lot of time thinking about risk–what it is, how one decides whether or not to take it, what it used to be. The only logic of these past weeks has been a kind of dream logic. I am floating; I am holding my breath; I am a sunken stone. When I scream, no sound comes out. You don’t think to notice the wrist unadorned by a hospital bracelet, the toe without a tag.

Every day when I walk, crest a hill, and am greeted by a gust of wind, I like to imagine it blowing through me like a gutted house. My body becomes skeletal–all bones and no flesh–sacred as a ruin. Did James Spader just ride past me on a bicycle? I can’t tell because he was wearing a mask.

My six-year-old tells me to feed her stuffed swan Kung Pao chicken. The roses already look ragged, but this is the most beautiful spring I’ve experienced. The scent of baking bread emanates from one house; fabric softener, from another. I try not to take my daughter’s new preference for being read to by a robot personally. Everyone I see houses panic in their heart. The sirens are faint enough to be mistaken for birdsong.

I teach my daughter how to draw a star. I also neglect her. I cannot remember if I took my medicine. I play tag. I’m not very good at tag; I don’t like it. My daughter really wants me to watch Pup Academy. I don’t want to watch Pup Academy. I want to barter away my soul by scrolling through my phone, instead. I find nothing there that I need.

I keep opening my day-planner to March, even though it’s May, because that is when time stopped for us. I don’t know how to keep a record of these days, but it seems important to try.

Life under quarantine

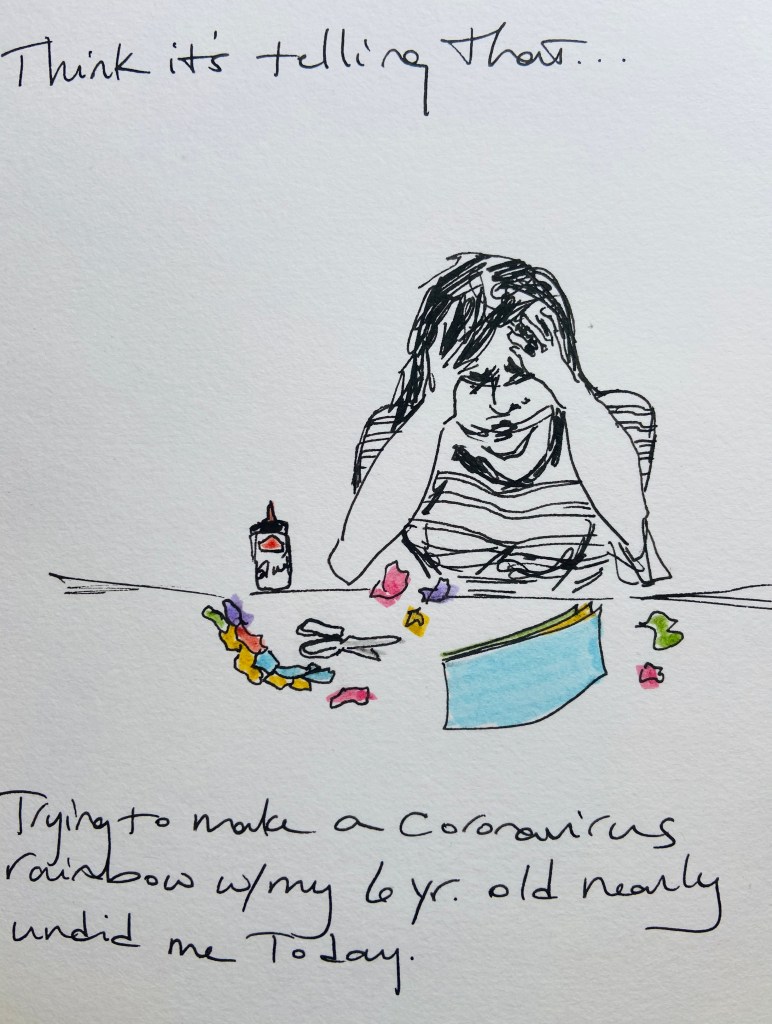

What, exactly, does it tell us? Several things:

- Even the simplest tasks are performed under a pervasive general strain on all of one’s faculties during this bizarre, sad, and maddening time.

- I am well enough, and my daughter is well enough, to undertake such simple, ostensibly heartening tasks.

- Somehow, we have an abundance of construction paper, but a dearth of the other kind (see below).

- I remain a perfectionist when it comes to many things, even under the shadow of a pandemic that, it would seem, might provide a welcome opportunity not to be SO. DAMN. ANAL.

- My daughter and I have creative differences.

- Our ability to reconcile these differences and complete the friggin’ rainbow has become an internalized metaphor for–and imagined predictor of–my own ability to get to the other side of this day, week, month, etc. in one piece.

As of right now, the rainbow remains… in progress. Will (try to) report back.

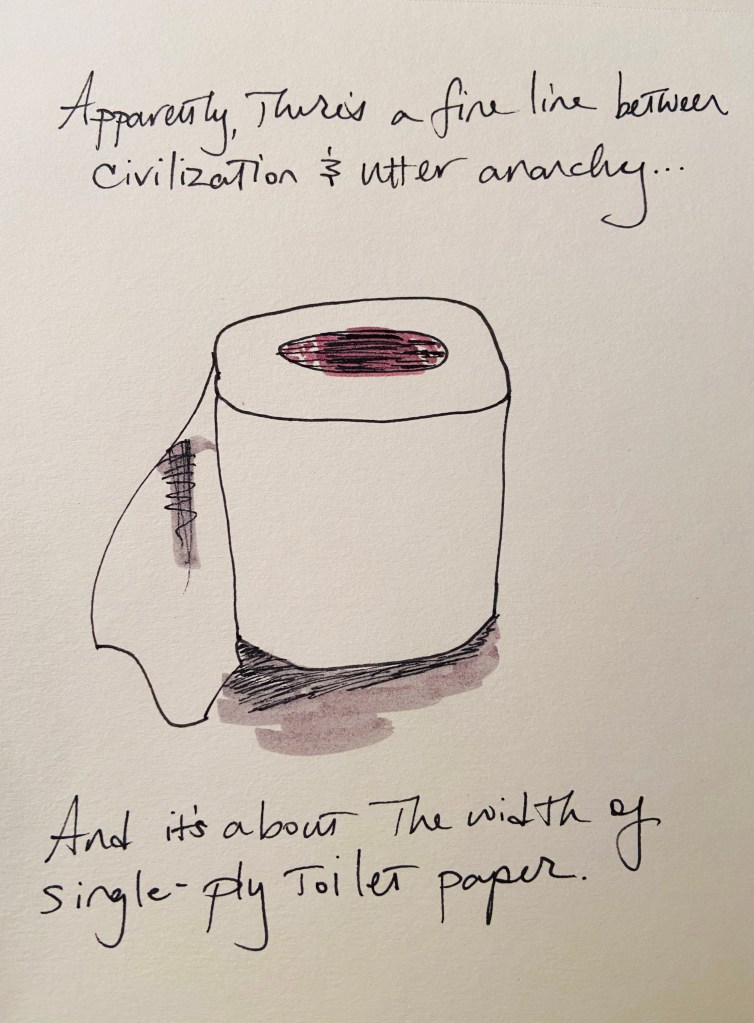

Who needs a cartoon?

The other day a student asked me, why the insane demand for toilet paper in the midst of this coronavirus outbreak? My reply: It’s symbolic, of course.

Friday Night News

Clear scan, full heart, can’t lose. Feeling profound relief today.

We’re not always wearing war paint

sometimes my body reminds me

that I am in it

the walls of your veins are thick

she says with annoyance

shouldn’t they be? I think with the same

the nurse is nonetheless kind (if also

impatient)

I recline in the chair, my head turned away

from the tourniquets and needles

and weep

which happens almost involuntarily now

whenever I am back where it all began

a year ago or so

as though in this position, passive and supine,

when things are being done to me

I finally have permission (or maybe it’s

privacy) to feel

everything I wouldn’t let myself

before

or

in-between

Birthday Greetings

Yesterday I turned 40. Cancer has changed my relationship to many things, time being first and foremost among them. I welcomed this birthday with elation, despite the fact that this particular age is dreaded by many. There’s no shortage of over-the-hill/you’re now officially OLD cards and other doomsday paraphernalia out there heralding one’s transition into a new decade (be it 30, 40, 50, or beyond), and I know, from observing those around me, that aging can be an especially fraught experience for women. There is so much cultural currency in youth and beauty–indeed, women often seem valued for these things, alone–that losing them is a terrifying prospect. But, after cancer, I can’t imagine begrudging a single birthday from here on out.

I covet all the years.

Brave New World

The other day, I attempted to log into a medical website to retrieve some lab results. I hadn’t been on the site in quite some time, so I found myself cycling through a number of usernames and passwords before I was finally prompted to answer the inevitable series of security questions. One being, “At which of the following addresses have you never lived?” I stared at the list of street names and numbers like a student taking a particularly vexing multiple choice test. Suddenly, my itinerant twenties flashed before my eyes, simultaneously vivid and vague. There were kitchens the size of closets; plaster walls I had illegally painted; the coin-operated washing machine in need of an exorcism; a back door that jammed every time I let my roommate’s dog out (god, how I hated living with that animal); the set of dishes I’d bought with my first live-in boyfriend; musty foyers and musical street sounds–all of these things conjured, in heady detail, by a simple list of names and numbers. And yet… Had I ever lived on Ramsay Ave., I wondered. If so, is it really possible to have forgotten such things already? My grasp of my own history felt suddenly tenuous. Where did LabCorp get this information, all of which pertained to years long before I’d become a patient in its system? More disturbingly, why did it seem to recall what I could not? I sensed a strange transfer of authority at work in all this, from myself as the repository of my own life and history to this other interface–an interface we now associate with untold hoards of data and memory, like some medieval dragon jealously guarding its treasure. I continued to mull over these questions after I’d finally accessed my results (which, thankfully, were normal, but unrelated to my cancer), before arriving at a different one: Is it a gift to have lived long enough to forget these things–namely, where one lived, and when, and with whom? Is it not a sign of life’s marvelous density, and/or of forgetting as a kind of mercy? I’m not sure such questions would have occurred to me before this past year–before cancer.

A few days later, I found myself reading The New Yorker on my phone, and was stopped in my tracks (or, rather, scroll) by an ad that had popped up mid-article. Usually, I find these noisome and utterly off-base (I’ve never been in the market for a neon hunting vest), but this one hit eerily close to home. It was an ad for wigs. I caught my breath. Again, I found myself wondering, what does the The New Yorker’s algorithm know that I don’t? Can my phone sniff out cancer like those specially trained dogs? Is this ad somehow prescient–is chemo in my near future? It took a while to walk myself back from the ledge of panic that this hardly innocuous little plug induced. I reminded myself that I frequently access this blog on my phone–in addition to searching for information about my particular kind of cancer–so it’s not altogether improbable that I would be targeted for such ads by marketers. And, of course, I’ve heard the stories of women who’ve received ads for maternity products before they’d even told family and friends they were pregnant. But that doesn’t change the eeriness of the experience. It dislodges one, somehow, from the locus of the self, and suggests that the self is, perhaps, a scattered collection of loci, to which many lay claim (LabCorp and Best Wig Outlet, apparently, among them). There is the me who has cancer now, just as there is the me who lived on NW 23rd St., years ago, cancer-free. The desire for some kind of cohesiveness, in the face of such fracturing, makes sense and has only grown stronger (in me, anyway).

Cancer’s weird consolations

This evening, I got my first haircut since February. My hair is fine and grows slowly, so I don’t get it cut that often. The last time I went to the same salon, I took off several inches in preparation for my surgery. My doctor told me that I wouldn’t be able to shower or get my incision wet for a few weeks afterwards, so I wanted something simple and low-maintenance. Tonight, I stared at the person looking back at me in the large mirror, strangely skeptical that it was the same one who sat in the same chair seven months ago. It’s funny how we can meet ourselves again and again in life. After certain things, in anticipation of others… The face in the mirror looked a little different, but what I felt was uncannily the same: fear.

It rises in me at regular intervals now, then recedes, like a tide. My first CT scan last Friday went surprisingly well until it didn’t. The nurse who stuck me for the contrast dye IV was incredibly kind and reassuring. She found my vein on the first try and, because it was only a scan of my head and neck, I didn’t have to drink that awful barium sulfate solution. My time in the machine only lasted about seven minutes, and my mantra had been well-rehearsed. Two hours later, my husband and I were back in the surgical oncologist’s office to go over the results. The nurse practitioner who met with us said that she’d looked over the images and didn’t see anything concerning. “We’re still waiting for the radiologist’s final report,” she explained, “but I think you should be good to come back in six months for your next scan.”

I felt profoundly relieved and dove into the pleasures of a three day weekend headfirst. Then, on Tuesday afternoon, I received the official report from the radiologist via my patient portal. Apparently, there was something concerning. An irregular lymph node in my neck that will need to be more closely monitored. I have to go back for yet another CT scan in three months instead of six.

This news settled hard, to the extent that it settled at all. I asked my doctor for more information; she responded that it is possible I just have an oddly shaped lymph node and, if there are no changes to it in three months, we can assume things are fine. But I’m still reeling from the last time I thought things were fine, and then they weren’t. I suppose this is the new normal, but damn, do I miss the old one.

As I’ve tried to wrap my head around this latest uncertainty–as I’ve moved through a range of emotions from shock to fear to rage to even, at times, forgetting–the consolation that has come to me is an odd one (unless, that is, you have cancer, or something like it). When I began worrying how I would get through the next three months of life and work without letting my pending scan–much less, what might be happening inside my body–weigh so heavily upon me that I might not be able to function, or when I felt sheer anger that I couldn’t have a measly six months out from under cancer’s shadow, I suddenly wondered why I was assuming I had those three months until my next scan at all. To most, this would seem an incredibly morbid thought, but, to me, it was a comfort. I don’t really know how to explain it, but when I first received my diagnosis (and little other information), and feared I might be dying as I drove home from having my blood drawn that day, it occurred to me that I could also die in a car accident at any time. And this offered the strangest sense of relief. I guess simply realizing that I still didn’t know, that all was as uncertain as it had ever been, created some space for hope. Which, though small, is where I’m trying to live for the better part of each day.

The postmodern poetry of pathology reports

For a time now, I’ve been able to put cancer behind me. I’m doing–and thinking about–other things. But this Friday, I have my first post-treatment CT scan, and it’s looming large on the horizon. I keep rehearsing the afternoon’s appointment in my head by recalling how things went down the first time. Drinking that awful barium sulfate solution, alone, in a freezing cold room; the brisk manner of nurses and lab techs; lying on yet another narrow table; feeling the contrast dye saturate my veins; repeating the mantra I said to myself, before, as the machine pivoted around me: My body is a dark city, my body is a dark city. Like London during the blackouts of WWII, I don’t want it to light up. (Obviously, my understanding of how these things work is vague, but I believe the radiologists are looking for some kind of “activity”–for cancer cells to react to the chemicals coursing through my body by luminescing.)

For some reason, my mind also keeps going back to my initial pathology report. I don’t know why doctors give these to patients; mine consisted of a dense paragraph of medical jargon followed by this stand-alone sentence, in all caps:

THE LESION IS MALIGNANT.

Reading it felt like the closest I might ever come to visiting an oracle. But what seemed, at the time, like a fixed decree–an intractable fate–has since revealed itself to be a bit more pliant. Much can still be done in the wake of such things; choices can still be made. Which may be why I’ve been questioning some of my own lately. Small ones, like becoming irritated in traffic, or with the endless stream of students filing into my classroom to borrow my stapler this morning. Do I, alone, have the earth’s last functioning stapler, I wondered. And then I took a deep breath, a proverbial step back. I do a lot of that now. Trying to notice how I’m responding to certain things and why. Trying to hold onto the perspective that the past nine months has brought, though it was dearly purchased (does perspective ever come cheaply?). Is this worth the worry or frustration it’s causing me? Can I let it go? We all have so many heavy things to carry. Friday’s appointment is one of mine.