I can’t possibly explain what’s happening–the strangeness of these quarantimes–so I’ll explain what’s happening (i.e. I cannot go on. I’ll go on). Some of it occurs outside, but much of it is inside. The earth keeps spinning, improbably, upon its axis. With the recent rains, we’ve discovered an abundance of tiny tree frogs around the deck. My daughter captures one or two each morning, and loses or releases them by the afternoon. We’ve also taken to walking them, like the dog we don’t have. It was her idea; she perches one on the thin metal stretcher under the canopy of her open umbrella and off we go. Slowly, of course, like 19th century flaneurs with their turtles. The frog grips the teeny, tiny rod with its teeny, tiny feet, rarely jumping or moving during our solemn daily promenade. I like to think they enjoy it, but of course I don’t know.

My husband listens to increasingly loud, experimental music when he’s in the shower. I think it’s an attempt to approximate his old commute, which now just involves walking downstairs.

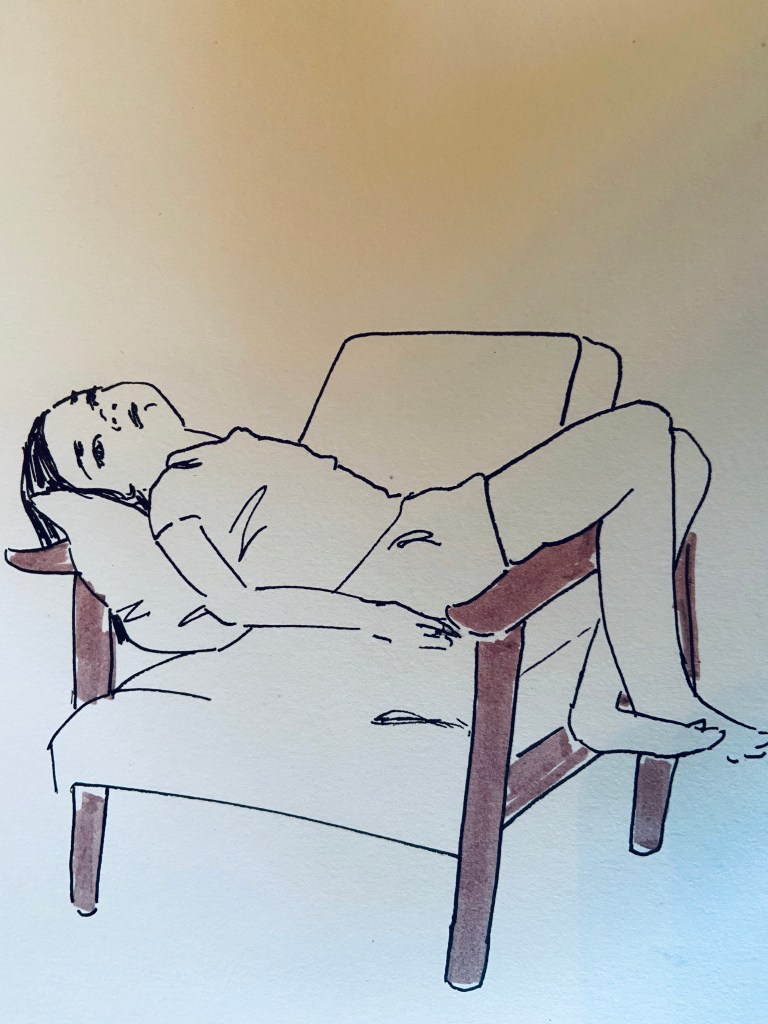

I often feel like lying face down in the road or someone else’s lawn, just to see if anyone stops to inquire after me, or to join in the prostration, themselves. I refrain from this, however. I refrain from so much.

We’ve made an anemometer out of toilet paper cores and plastic straws. We’ve learned what an anemometer is. We sit through the tedium that is virtual learning–my daughter’s school’s as well as mine. The voices of children, even online, are so lovely; their use of all caps in the chat box, so liberal. I envy them this.

The days feel bloated and amorphous, yet my desires grow sharp with specificity. My dreams, likewise, are laughably transparent. I ration the new Pen15 episodes like I did flour in March. Somewhere in all this, I got another clear CT scan and celebrated quietly. But it was not without bitterness and bemusement that I thought to myself, This was when I was really supposed to be living life, you know? After last year’s diagnosis and treatment and recovery… And so I am, such as it is.